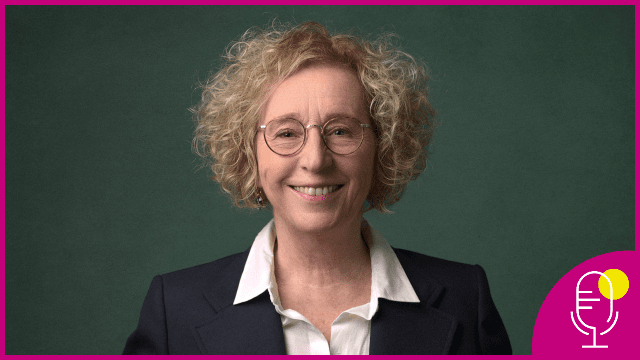

Muriel Pénicaud: “The future of work will be plural, uncertain, yet full of collective innovation.”

[This translation was automatically generated]

Former Minister of Labour, Chief Human Resources Officer at Danone and Dassault Systèmes, CEO of Business France and French Ambassador to the OECD, and now internationally active in corporate governance and discussions on the future of work, Muriel Pénicaud has consistently placed people at the heart of transformation. Faced with technological acceleration, demographic and environmental upheavals, and new generational aspirations, she calls for a deep rethinking of our models of organisation, education, and social protection. A daunting yet exciting challenge — one in which ESSEC alumni have a crucial role to play.

Reflets Magazine: You reject the idea of an “end of work”. Why is that so important today?

Muriel Pénicaud: Because this debate is an old one — and always misses the point. For decades, some have predicted the disappearance of work. Yet every serious study and credible scenario shows a profound transformation, not a disappearance. I don’t take an ideological stance; what matters to me are realities, risks, and opportunities. Work will change — radically — but it will remain an essential pillar of our societies, our collective life, and our personal and shared identity.

RM: You mention a “tsunami of work” by 2030. What does that mean?

M. Pénicaud: It’s not a catastrophist image. It’s a way of describing the unprecedented scale and speed of the transformations we are living through. What makes this period unique is the simultaneous convergence of four waves of change. First, artificial intelligence, already impacting entire value chains and particularly so-called “white-collar” or “cognitive” jobs — in law, finance, marketing, sales, and HR. Next, the ecological transition, whose impact on jobs — from production to consumption — is still underestimated. The third wave is demographic: an ageing North, a very young South, and growing tensions in labour markets that encourage professional migration. Finally, the relationship to work itself: across all countries, the hierarchy of priorities has shifted. Work is no longer necessarily number one in life. This change, accelerated by the Covid crisis, affects all social classes. This collision creates instability — but also an unprecedented capacity for invention.

RM: Is Europe — and France in particular — ready to face these transformations?

M. Pénicaud: We’re “midstream”, so to speak. Awareness is growing, but technological and skills investments remain far below what’s needed. On AI, there are big debates and a few champions. But if we don’t want to remain mere consumers of technology from the US or China, Europe must act collectively — and ambitiously. As for education and skills, we are falling behind: France has dropped from 5th to 25th place in PISA rankings. The skills level of the active population is also falling. We don’t invest enough in education, training, and innovation — yet that’s where everything begins.

RM: You advocate a strategic approach to transformation within companies. What does that look like in practice?

M. Pénicaud: It starts with clarity. Too few companies have taken the time to analyse what AI or the ecological transition actually mean for their jobs, processes, and skills. Where is value shifting? What is the human role in all this? Which jobs will emerge, disappear, or be completely reconfigured? These reflections must be placed at the heart of corporate strategy — not confined to HR or training. And we must understand that tomorrow’s skills won’t be “available on the market” — they will need to be created. This requires new alliances between companies, schools, universities, and training bodies. Stronger connections between initial and lifelong learning. It’s a huge challenge — but also a tremendous opportunity.

RM: You’ve spoken of a billion jobs being affected globally. How can we prepare for such a shift?

M. Pénicaud: We must first grasp the scale of the upheaval. Between 50% and 80% of jobs will be created, eliminated, or — for the majority — transformed in depth. Singapore, which plans ahead carefully, has estimated that it would take 120 days of training per worker per year if no new ways of learning are invented! That gives a sense of the challenge. We can no longer think of training as an occasional “course”. We must invent a model of work organisation that integrates agile, embedded, hybrid, iterative lifelong learning. Sixty-five per cent of today’s children will do jobs that don’t yet exist — an opportunity to reinvent the relationship between work and learning.

RM: Younger generations seem to reject old forms of engagement. What new social contract do you imagine?

M. Pénicaud: Permanent contracts, once the ultimate goal, are now often seen as a constraint. Some young people reject them, others set conditions — not out of disengagement, but because they seek autonomy, project-based work, and chosen flexibility. Many turn to self-employment, often without safety nets. In contrast, organisations remain rigid. The old hierarchical model no longer makes sense. We must invent a new 21st-century “flexisecurity”: guaranteeing portable rights, protecting without restricting, and recognising new forms of engagement. Above all, management must be rethought. Young people don’t want bosses — they want coaches. Inspiring figures who guide, support, recognise, and help others grow. Authentic, coherent leaders guided by purpose and empathy.

RM: In the face of automation, which human skills will be decisive?

M. Pénicaud: Everything that can’t be automated: creativity, cooperation, curiosity, empathy, emotional and practical intelligence. These essential dimensions of our brains — long considered secondary by education and management systems — will now create value. AI excels at analysis, repetition, transactions, and logic. It could save up to 30% of working hours. But it cannot cooperate, invent, or feel. Innovation, complex problem-solving, collective intelligence — all rely on “soft skills”. Today, according to the OECD, the average lifespan of skills acquired through professional higher education is just two years. In 1987, it was 30 years. This means that what matters is not only content, but the ability to learn — to combine our three forms of intelligence: analytical, creative-emotional, and practical. The last of these remains largely underestimated.

RM: How can we prepare people for jobs that don’t yet exist?

M. Pénicaud: First, by helping everyone understand how these technologies work, and developing their skills so that they can choose, not endure, their professional lives. That was the purpose of the Personal Training Account (CPF), which we opened to 30 million workers in 2019. One key challenge is ensuring everyone understands the basics, biases, risks, and opportunities of AI. We can’t question what we don’t understand. We must learn to ask the right questions, examine sources, and think critically — the art of the “prompt”. Teaching is becoming Socratic again. We must also rethink retraining. I love the example of Montreal’s University Hospital: thanks to AI, they gained 30% productivity in logistics. Instead of cutting jobs, they reinvested that time into human interaction with patients — improving care quality and recovery rates. Those are the kinds of strategic choices we need to generalise. Value is shifting back to humans.

RM: You chose to use a graphic novel to explore these ideas. Why?

M. Pénicaud: Because I wanted to reach a broad audience — across generations and social backgrounds — and spark a public conversation about the future of work, which concerns everyone. The graphic novel is a powerful medium: it makes complex subjects accessible without oversimplifying. Together with co-writer Mathieu Charrier and illustrator Nicoby, I interviewed a wide range of figures — Christine Lagarde, Thierry Marx, Marylise Léon, and others — who agreed to become characters in the story. We built a fictional narrative around Soraya, a high-school student investigating the work of tomorrow. It’s lively, human, well-documented, serious yet humorous — and it sparks dialogue. Many readers told me they bought extra copies to discuss it with family, and businesses and professional networks are sharing it to open discussions with their managers and teams. That was exactly the goal.

RM: What worries you most — and what gives you hope?

M. Pénicaud: What worries me is that we keep applying old reflexes to unprecedented transformations — cutting costs instead of innovating, underinvesting in European technological sovereignty and education. I fear that AI could deepen inequalities, strengthen social control, and weaken democratic debate — and that we’re not updating our mindset fast enough.

But what gives me hope is the energy I see everywhere — in companies, in schools, among young and older people alike. There’s a desire to build, to experiment, to do things differently. If we break down silos and make technology and humanity, seniors and juniors, work together, then yes — we can make work a powerful driver of collective progress.

RM: What role can ESSEC alumni play in this transformation?

M. Pénicaud: A crucial one. As leaders, entrepreneurs, and innovators, they can be at the forefront of this transition, each in their own sphere of influence. But only if they avoid staying among “clones”. We must mix generations, disciplines, and experiences — bring together tech experts and HR, strategists and practitioners, business and civil society. Real innovation will come from that hybridisation.

To read: Travailler Demain, Muriel Pénicaud (writer), Mathieu Charrier (co-writer), Nicoby (illustrator).

Éditions Glénat, €24

Interview by François de Guillebon

Comments0

Please log in to see or add a comment

Suggested Articles